Who Can He Be?

Dating Evidence

In 1988, three radiocarbon laboratories dated samples of the Shroud of Turin and boldly announced that it was a medieval forgery, dating to the period 1260-1390AD. This conclusion was completely incompatible with the findings from the previous ninety years of Shroud studies, but as far as the radiocarbon scientists were concerned, and most of the world’s media, this was now the only evidence that mattered.

This dating result and the conclusion that the Shroud was a medieval forgery made headlines worldwide and was devastating news for the millions who had believed the Shroud to be a sacred relic. However, it wasn’t long before details emerged revealing how this test had fallen short of acceptable scientific practice, with several breaches of agreed test protocols and a controversial statistical interpretation of the dating measurements. Sadly, these revelations failed to generate a fraction of the publicity given to the controversial C-14 dating result.

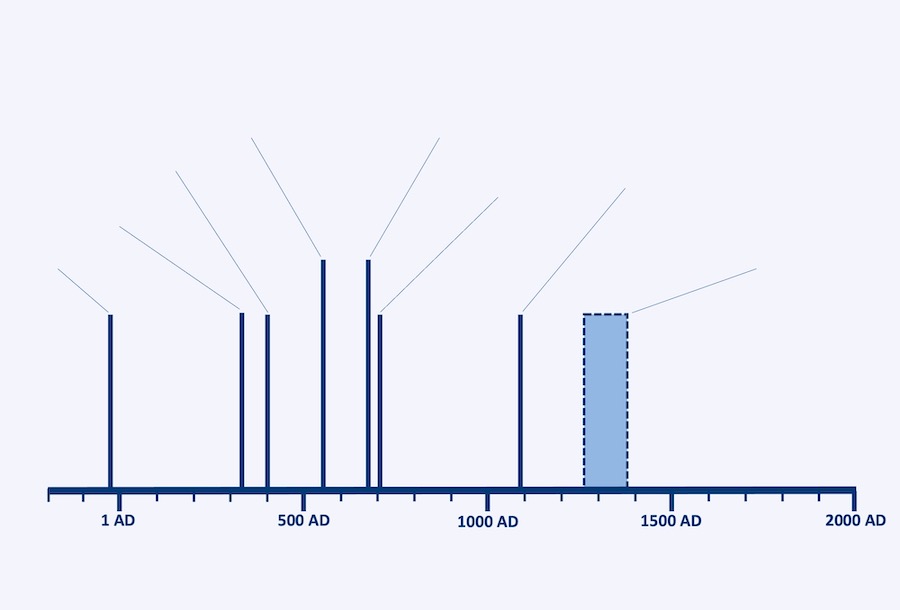

Fortunately, there are other ways of determining the age of historical objects. There are a number of very distinctive markings on the cloth, such as the body and facial images, wounds, bloodstains and scorched areas. Various historical artefacts have been discovered which have an extraordinarily close match to some of these features, including iconography created by artists who appear to have copied from the Shroud. We know the age of many of these artefacts and these effectively provide date-stamped snapshots tracing the Shroud’s history. Scientists have also developed new and innovative ways of measuring the age of ancient linen fabric which have been used to date small samples of material from the Shroud.

You can access details of this dating evidence from the timeline below. As you will see, there is overwhelming evidence that the Shroud of Turin is much older than the C-14 test indicated.

Dating Evidence Timeline

Coins over the Eyes?

In 1980, Professor Francis Filas of Loyola University in Chicago and Michael Marx, an expert in classical coins, detected patterns on coins which had been placed over the eyes. The coin on the right eye appeared to be a lepton, a coin minted between 29 and 36AD by Pontius Pilate the Roman Governor of Judea which depicts a staff circled by the words TIBERIOU KAISAROS. When viewing photographs of the Shroud at high magnification, Filas identified the staff and the letters UCAI. This almost matched the lepton coin but curiously the letter C was found where he expected to see a letter K. This initially undermined his findings until two lepton coins with exactly the same misspelling came to light.

This was regarded by many as a particularly important discovery as it appeared to confirm the presence of the Shroud at both the time and place of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ. However, several scholars have doubts that it was the custom in first century Jewish burials to place coins over the eyes of the deceased, particularly pagan coins celebrating a Roman Emperor. Shroud scientists who specialise in photography and image processing have also questioned the photographic processing that was used to reveal the alleged lepton markings. Filas had made progressively enlarged, high-contrast copies of an original 1931 photograph taken by Giuseppe Enrie, a process which produces clumps in the grain structure of the film that can alter the image. In addition, some of the markings appear to correspond to threads in the weave of the Shroud.

The reliability of the coin evidence discovered by Professor Filas has clearly been undermined by the opinion of these experts. However, until it is proven that there aren’t any discoloured fibres which correspond to the alleged lepton markings, the possibility that coins were placed over the eyes of the Man of the Shroud cannot be dismissed.

Performco Ltd. Town Hall, Penn Road, Beaconsfield, Bucks HP9 2PP

Copyright © Performco Ltd.